The years of the Vietnam War have been called one of the most turbulent periods in our nation’s history. Our soil became a battleground of the American spirit; an era of vast anti-war protests and demonstrations in which University President Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., found himself taking a stand. College campuses nationwide were sources of unrest. A series of on-campus protests from 1969 through the 1970s culminated in the "Seven Days in May."

Established by Hesburgh, the now well-known 15-minute rule set a series of guidelines for the conduct in which future student protests will be held on campus. The eight-page letter written by Hesburgh on February 17, 1969, to faculty, students and their parents outlined the University’s action against “anyone or any group that substitutes force for rational persuasion be it violent or non-violent.” Hesburgh said that such persons “will be given 15 minutes of meditation to cease and desist;” those who did not would face immediate suspension, expulsion and/or removal. Attracting national attention, Hesburgh’s office received more than 1,000 letters and telegrams which commended his position, and a condensed version of Hesburgh’s letter was printed in the New York Times.

Tensions over the U.S. involvement in Vietnam continued to rise and the chain of events that followed the next year changed the nature of the student protest era at Notre Dame. Hesburgh’s 15-minute rule was put to the test on November 18, 1969, when Dow Chemical Co. and the CIA were at the Main Building for student recruitment interviews. Student activists lined the corridor in opposition of Dow, who produced napalm, a weapon used in Vietnam. While many adhered to the rule, a group of students dubbed the “Notre Dame Ten” did not. After 15 minutes, Rev. James Riehle, dean of students collected the IDs of those ten students of whom five were suspended and five expelled. The ruling was changed however so that all ten received suspensions.

The following spring, April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon announced his plans to invade Cambodia, expanding the Vietnam War. The news sent shock waves nationwide, particularly to college campuses. The Board of Trustees subsequently arrived on campus the next day and was met by a small group of students attempting to disrupt their formal meeting held in the Center for Continuing Education. The protest failed to garner a larger student audience compared to several hundred students who gathered on the main quad for “Free City Day”, a day to reflect upon one’s education and educational reforms. The peaceful student gathering quickly turned contentious as talk progressed to the use of American soldiers in Cambodia.

On May 4, student organizations rallied approximately 2,000 students to gather on the main quad. Organizers invited Father Hesburgh to open the program, which he did with a handwritten statement he drafted earlier that morning. The same day in the neighboring state of Ohio, the American spirit was hardened once again when news broke about the shooting death of four students by the National Guard at Kent State University. Hesburgh spoke with courage to the sullen student body as word made its way throughout the crowd of what is now known as the “Hesburgh Declaration.” His six-point declaration called on President Nixon for the “withdrawal of our military forces at the earliest moment” and work toward “renewing the quality of American life.” Although Hesburgh requested that classes not be stricken down, student activism reached an all-time high as student focus turned to directing action for peace. Immediately after Hesburgh’s speech, the student body president proclaimed a student strike and strike they did… for seven days. Nearly half of the student body boycotted classes to protest the U.S. action and placed flyers across campus displaying a raised green fist and the words "Strike Irish." T-shirts with the same design were also sold at “Strike Central” in LaFortune Hall.

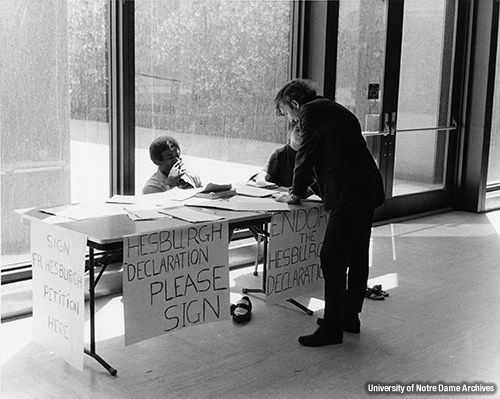

The “Seven Days in May” culminated in a demonstration in front of Memorial Library where students gazed toward the arms of Christ reaching out as they stood for peace. Inside the library concourse, students sat at a make-shift station gathering signatures from students and faculty who voted to endorse Hesburgh’s Declaration. They eventually made their way to residents from the city of South Bend and at the end of the campaign, 23,000 persons signed the declaration.

While springtime dissent fell on other college campuses, make no mistake, our student activists stood out as the peacemakers. ND students opened two counseling services in the study rooms of Memorial Library. Every event and gathering during those seven days was resolved peacefully. Students attended a mass on the holy day of Ascension Thursday, participated in the “communiversity” teach-in discourse in dorm halls and packed the old Fieldhouse to hear a New York congressman share in their conviction to end the war. These events contrasted starkly with campus unrest at the University of Illinois where the agriculture section of the library catalog burned.

The Library Faculty who attended an emergency meeting during the seven days of May felt a new unity among themselves for participating in the democratic process. In the end, the library faculty offered to enlist undergraduate support in bettering library service for the next year.

For more information:

Hesburgh Letter, The New York Times (1969)

Campus activism: Then and now. ‘Notre Dame 10’ return to campus to honor 40th anniversary of Dow-CIA demonstration.